Trio of Mountaineers

forged new routes

in the North Cascades

Ten Days on Mount Terror

by H.V. Strandberg Sr.

| Pioneering the Pickets Trio of Mountaineers forged new routes in the North Cascades

Ten Days on Mount Terror |

Editor's note:

This month, Echoes offers the concluding installment of an epic initial exploration of the North Cascades. The July issue chronicled the first ascents in the Upper Skagit River valley by Herbert V. Strandberg (1901-83) and William A. Dagenhardt (1902-56). They returned the following summer with James C. Martin (b. 1908) to ascend the peaks of the Southern Picket Range that they had first glimpsed in 1931. This article by Strandberg appeared in the 1932 Mountaineer Annual. Martin remembers Strandberg as the organizing force behind their climbing trip, while Degenhardt took responsibility for all their food. Martin describes himself as just "part of the freight."

Approximately twenty-four miles east of Mount Baker, we find a group of peaks appropriately named Mount Challenger, Mount Fury, Mount Terror and Pinnacle Peak, which collectively make up the Picket Range. This range extends from Whatcom Pass on the north to the Skagit River on the south. . .

A glimpse of Mount Terror is to be had as one passes the mouth of Goodell Creek, on the City of Seattle's Skagit Railway, not more than two miles from Newhalem. Goodell Creek is named for N.E. Goodell, a miner and horse packer in the North Cascades in the 1880's. It was this fleeting glimpse and the apparent lack of information about this region which prompted Bill Degenhardt and me to make a short reconnaissance trip in August, 1931. The information gained on this trip formed the groundwork upon which we planned a second expedition.

James C. Martin, Wm. A. Degenhardt and I left Newhalem on Sunday,

August 7, 1932. We carried with us food for two weeks, together with ice

axes, climbing rope, tennis shoes, prismatic compass, aneroid barometer,

and cameras. Jim Martin remembers that their ice axes had long shafts,

"like walking canes." They wore wool clothing and carried a single hemp

rope. The tennis shoes were for rock climbing after they had surmounted the

glaciers. Martin had a down sleeping bag with a waterproof cover that he

carried, rolled up, on the top of his metal-framed pack. Each carried a tin

cup on his belt for food and beverages. Their diet included rice, beans,

and macaroni. They also had chicken packed in glass jars. Martin

particularly remembers a dehydrated split pea soup that they ate almost

every evening. It was in the shape of a dynamite stick; they just broke off

a piece and boiled it. The soup was called "herbswurst," not, Martin

explains, named for his companion Strandberg. Degenhardt did all the food

planning, and the weight of their loads meant that they did not carry extra

meals. Martin recalls the bale on their cooking pot breaking while over the

campfire, and Degenhardt salvaging beans from the flames.

We planned to work our way north along the Picket Range to Whatcom

Pass, thence down the Little Beaver to the Skagit and back to Newhalem, a

plan which we were later forced to abandon. The easiest, or rather, the

least difficult approach to the south end of the Picket Range . . . lies up

Goodell Creek. A good trail extends five miles up the creek to Gasper

Petta's cabin. . . Petta, a Greek immigrant known as Jasper, was a trapper

who sold his pelts to Sears for $50-75 each. Jasper Pass, at the head of

Goodell Creek, is named for him.

Camp was made in a group of six large trees at timber line a half-mile southeast of Pinnacle Peak. It rained almost continuously while we were camped here. Before we left, we had a bough lean-to built under the trees. The climbers carried no tent, relying on the normally favorable August weather, a miscalculation that season. They slept on bough beds, before this practice became environmentally incorrect.

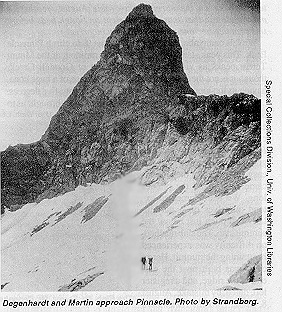

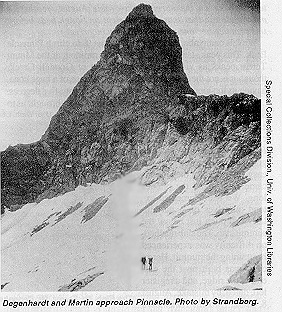

We left camp about 1:30 p. m., August 9, to climb Pinnacle Peak.

This peak stands out as the most prominent of the Mount Terror peaks as

viewed from the mouth of Goodell Creek, though it is not the highest. It

has the appearance of a huge cone, having its top lopped off at an angle of

about twenty-five degree.

An hour's climbing over granite slabs and snow brought us to the

base of a chimney in the east face of the peak. This chimney was easily

negotiated for some two hundred feet. The going from there on was not easy,

however, for the face became slabby and the pitches long. We were forced to

extend ourselves on a particularly bad pitch just below the summit slab.

The slab reached, no difficulty was experienced in attaining the summit.

Here a cairn was built near the east end of the ridge, and a register left,

dated, by mistake, August 8, 1932. Jim Martin remembers that the climbers

drank dehydrated coffee with the brand-name "G. Washington." As they

emptied the cans, they used them for summit registers. . . .

Turning our backs to Mount Despair, we look off to the East.

Immediately below us is a new field, probably three quarters of a mile

across, sloping gently upward to the rim of Crescent Creek Basin. . . It

terminates to the east in that vertical wall which forms the west wall of

Terror Creek, and extends almost its entire length.

This wall we have called the Barrier. It is from 500 to 1,500 feet

high, and almost unbroken for its entire length. We spent one day last year,

and almost two days this year trying to find the way down into Terror Creek,

or onto the glacier above. In those places attempted, the chimneys ended in

a vertical face, and in the places where it was possible to negotiate the

rock, it was impossible to get from the rock to the ice. In 1931, Bill

Degenhardt and I crossed the Barrier at a point near the head of the

glacier. Fortunately, it was freezing at the time, and we were not bothered

with falling rock. During the day, when the snow is melting, rock and snow

keep falling from pockets in the cliffs above, making this route extremely

hazardous, except when it is freezing. As it turned out, this falling rock

was the only thing that made this route possible because it bridged the gap

between the rock and ice.

Across the Barrier and Terror Creek beyond, we see the long ridge

which terminates at Newhalem, and beyond it one snow-capped peak after

another, many over 8,000 feet high. At the head of Terror Creek, are

several imposing rock peaks, which form the Terror-McMillan Creek divide.

These peaks seem to have only two dimensions--width and height. These would

offer most difficult climbing, in fact we might, without much danger of

contradiction, say that these peaks are impossible to climb. . .

Wonderful as the views to the west and east from Pinnacle

Peak are, they cannot be compared with that to the north. A mile and a half

to the northwest, is what we shall call West Peak aneroid elevation 7,300

feet. Strandberg's aneroid barometer was an early altimeter that measured

altitude by means of a vacuum and a mechanical indicator. It took a half

hour to get a reading, which they did not always have to spare. Strandberg,

the surveyor and mathematician, devised a formula for estimating their

altitude. It occupies much the same position with respect to the Crescent

Creek Basin as Pinnacle Peak. The basin is like a huge stadium open to the

west. Pinnacle and West Peak guard the western end. A long ridge in the

shape of a horseshoe connects these peaks. The ridge is nearly three miles

long, and consists of one sharp pinnacle after another rising from one

hundred to five hundred feet above the general level of the ridge and from

five hundred to two thousand feet above the snowfields and glaciers about

its base. They increase in height progressively to the east, the highest

being the true summit of Mount Terror aneroid elevation 8,360. The sheer

pinnacles standing side by side may have looked like a picket fence to early

pioneers, hence the name Picket Range.

The rock is, in general, granite, in some places weathered almost

black, in others gray, almost white, while in other places the rock is

stained deep red and brown. The floor of the basin is steep, and in winter

it is the scene of many avalanches, of which new scars near the tops of

trees give mute evidence. Between 5,100 and 6,500 feet, the basin is like a

huge rockery, alpine flowers of all kinds growing between rocks and

boulders. Within a hundred feet of camp were some twenty varieties of

alpine flowers in full bloom, a delightful contrast to the rugged peaks

about. Our camp (elevation 5,300) was located at timber line close to the

creek and above a big boulder. A month could be spent in this basin and one

could climb every day and never go up or down the same chimney or climb the

same peak twice, and every day would give a good climb. On this expedition,

we had time to climb only a few of the outstanding crags.

On August 16, we climbed West Peak. . .From the top we had a most

unusual view. The sky above was perfectly clear. Below, at elevation 6,000

feet, a sea of clouds extended in all directions, broken only by rugged

peaks, mere islands in this sea of fog. Jim Martin's enduring memory is of

the fog moving inland from Puget Sound, "spilling over the ridges like

water." We spent fully three hours on the summit, taking pictures and

locating peaks by compass. Bearings were taken on about forty of the more

prominent peaks, including Three Fingers and Whitehorse near Darrington. Far

to the southwest, the Olympics could be seen, a range of mountains on lthe

horizon. To the north, Mount Fury rises almost vertically from the depths of

Goodell Creek. A mile below us, through a break in the clouds, a silver

thread marked the course of Goodell Creek as it turns sharply to the

southeast on its way to the Skagit. To the northwest, we saw the lake which

lies in the pass at the head of Picket Creek, a tributary of the Baker

River. It does not seem possible that this pass can be approached from

Goodell Creek, as that side of the creek appears to be almost a solid

unbroken slab of granite of great height.

The view of the Mount Terror group, which is the rim of Crescent

Creek Basin, is ample reward for making this climb. A little more than a

half mile to the east are the two needles which stand so prominently

against the sky as one looks up Goodell Creek from the Skagit, or as viewed

from Pinnacle Peak.

On August 17, we climbed the one to the west. These afford some

most interesting climbs since it is impossible to plan a route to the

summit from below. The face is broken with chimneys running in every

direction, all extremely steep and full of chock stones. After entering any

of these chimneys from the glacier, little is left but to climb upward,

trusting that a continuous route to the summit can be found. We climbed a

long chimney which runs diagonally up the face. This chimney was found to

be continuous, except for an occasional steep grass slope ending in

vertical cliffs below. It is only 1,500 from the glacier to the summit,

(elevation 8,000), but it required almost six hours to make the ascent. . .

From the top, one could look almost vertically down on the McMillan Creek

glacier, a glacier of considerable size not shown on any maps. An excellent

view of the summit of Mount Terror is had, and to its right, the peak

climbed in 1931 by Bill Degenhardt and me . . .

The location of the summit of Mount Terror is somewhat indefinite

on the map. We assume that it is intended to be the highest of the peaks in

this group. Viewed from Pinnacle Peak, it appears as a pyramid, almost

vertical on the right, or east side, and sloping steeply upward from the

summit ridge on the west.

The route we followed, and probably the easiest one, can be seen

from this point. A snow-filled chimney leads up to a notch in the ridge

just west of the peak. This chimney is about six hundred feet long and is

very steep. After reaching the notch, we spent half a day trying to get up

the pitch immediately above, and it was only on the fourth attempt that we

succeeded after again resorting to tennis shoes. Our fourth attempt took us

through the notch to the snow on the far side, from which we had to jump to

a narrow ledge where the change of shoes was made. We then climbed nine

hundred feet in elevation along the summit ridge to the top. A cairn was

built about forty feet below the top, because the top was not large enough

to support such a structure. . .

The last day in Crescent Creek was spent in one last effort to

cross onto the glacier at the head of Terror Creek and reach those peaks on

the McMillan-Terror Creek divide. In this we were unsuccessful and we were

forced to abandon our revised plans of going out over Ross Mountain and had

to return by much the same route as used on our way in The rugged slopes

by this time had taken a toll on men and equipment. Martin remembers Bill

Degenhardt sitting on a rock in Goodell Creek, trying to restore his

climbing pants by pinning a bandana into what was left of the seat. Martin

spent more time in Degenhardt's company than Strandberg's. He remembers

Degenhardt as a wonderful storyteller who was always asked to describe his

climbs at the Wednesday evening Mountaineers club meetings. . . .

We saw no signs of anyone having been around these mountains before

us. . . Those who like to explore the unknown will find it of extreme interest.

An editorial observation: One marvels at the level of risk that Strandberg, Degenhardt, and Martin assumed. A single misstep, a disabling injury, and no help was in sight. No radio, no cell phone, no mountain rescue, and no helicopters; they were operating without a net. While their first ascents are comparatively easier with modern equipment and training methods, their daring was nothing less than heroic.

© 1998, The Mountaineers

Climb Up to Top Back

Back